"I Am the Walrus / Goo Goo G'Joob"

- Rhett Blankenship

- Jan 6, 2021

- 5 min read

On a beach lit by both the moon and the sun, a carpenter and a well-dressed walrus walk along the shore and dine on oysters. This is the central image of the poem aptly titled "The Walrus and the Carpenter" in Lewis Carroll's 1871 Through the Looking-Glass. This fictional image of the walrus as an eccentric-looking whiskered creature with tusks as large as its appetite also represents perhaps the best-known depiction of walruses in English literature and has come to find itself reproduced in other English cultural artifacts, from film to television to song—I'm looking at you, Lennon-penned Beatles B-side "I Am the Walrus" (1967).

The English understanding of the walrus is as interesting as it is far-reaching. What makes the English walrus most intriguing, though, is its relationship with reality; the English walrus is as rooted in reality as John Lennon's declaration, "I am the walrus / goo goo g'joob." Lennon, Carroll's walrus, and the English walrus are not really walruses. In short, no English-language walrus is a real walrus, because any walrus in the English language is less a walrus than a placid caricature of a creature or a compilation of parts capable of being separated and used for economic gain.

The very first recorded instance of a walrus in an English-language text occurs in William Caxton's 1482 Chronicles of England. Caxton, a merchant and the first English book printer, reveals the walrus, then the morse, or rather, "mors marine," in a rather bland manner: "This yere were take iiij grete fisshes bytwene Eerethe and london, that one was callyd mors marine." Not exactly the robust beast of the sea that the indigenous peoples of the global Arctic and Northern Europe had been encountering and describing in their societies for centuries at this point. In fact, under the English name of morse, the walrus is a relatively docile albeit odd creature that will soon become known only for its tusks.

The Northern European Rosmarus/Rosmaro

Contemporaneous with its identification as the morse in English, the walrus was being called by its Scandinavian and Dutch name rosmarus or rosmaro in histories, bestiaries, and maps in many other European languages of the time. A terrifying tusked beast prowling the Arctic waters and dangling off cliffs from their long teeth to slumber, the rosmarus/rosmaro was the rest of Europe's attempt to understand the walrus, a strange northern creature which they—unlike the English—happened to perceive as being a ferocious mankiller.

We get a glimpse of fang—or tusk, really—from the morse in the mid-1500s by Richard Chancellor on one of his voyages when he came into contact with a man wielding knives fashioned out of the "teeth" of a "fish . . . called a Morsse." We again see the tooth of the morse appear in James Hall's 1625 Voyage to Greenland; this time, though, the tusk of the morse is not merely a material object and tool but also an economic resource: "[T]he people [came] to us, and barter[ed] with us for . . . Morse Teeth." Beyond mentions of the morse as a source of tusks capable of being used for economic gain, the morse can also be found in literature. It appears in Robert Browning's 1840 narrative poem Sordello to describe the Northern Europeans most associated with the creature, but even here it cannot escape reference to its tusks: "Those tall grave dazzling Norse, / clear-cheeked, lank-haired, toothed whiter than the morse."

In 1728, long after the morse had entered the English language but around a century before it had broken into English literature, the tusked Arctic creature in question began to be referred to by its current English name of walrus. For about a century, then, the walrus was known and spoken of under both names in the English language, and both names produced an image of the walrus which focused solely upon its tusks and what could be gained from them.

Perhaps it is fitting, then, that a culture that has been fixated upon the material existence and worth of the walrus tusk should have its first appearance of the walrus under the name of walrus be ushered in by its tusk. Debuting in John Woodward's 1728 A catalogue of the additional English native fossils as an entry in his attempt to inventory his expansive collection of English fossils, the walrus is welcomed into the English language as a fossilized tusk under the section "Bones, Teeth, &c. of Fishes." More of the same treatments of the walrus occur over the 150 years that follow as it appears in various British and North American natural histories, geographies, and recountings of arctic explorations, solidifying the materialistic perception of the walrus as being defined by its ivory tusks.

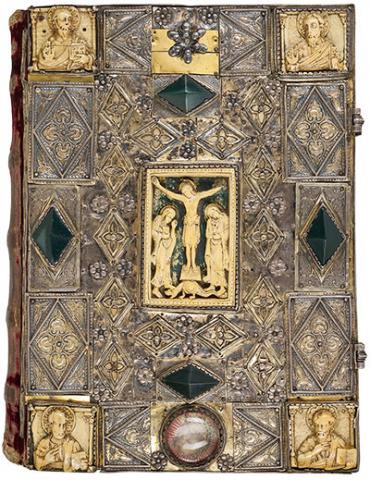

Regarding the use of walrus ivory in bookbinding, interestingly enough, the practice seems to have been most popular in Germany during the Middle Ages, though was also occasionally used around the same time for such purposes in Denmark, England, and France. These Medieval usages of walrus ivory in bookbinding, despite being geographically and linguistically scattered, share a common application: ivory was hand-carved into adornments used alongside precious metalwork and jewels in the practice of treasure binding Christian holy texts. Though not many books exist with walrus ivory baubles today, there are enough artifacts from earlier periods to claim that the material was indeed used for this purpose across Europe. Slide through the gallery of images below to see some examples of books treasure bound in walrus ivory:

The thick hide of the walrus has also been used as leather binding for books, but the practice was recent and considered a form of what journalist Holbrook Jackson called "bibliopegic dandyism," or the pursuit of exotic materials for usage in bookbinding. As such, physical copies of walrus leather books are virtually impossible to find, but their existence is able to be proven in advertisements from the turn of the twentieth century. For instance, the 1899 edition of The Delineator, a New York women's journal of culture, claims that the memorandum book is a practical gift that is now being bound in the leather of "Texas steer, walrus, rhinoceros, elephant hide, or monkey skin" and would be the perfect present for a female friend. Just nine years later in the May 21, 1908, publication of The Winnipeg Tribune, "walrus leather book covers with convenient handle and bone paper cutter" are listed as being on sale at a local shop. And so it seems that even from the Middle Ages up to at least Lennon’s declaration of walrus-hood, the walrus has never truly been seen as whole in the English language; rather, when invoked in English, it has only ever been seen for what it can offer the Western consumer—a pair of precious ivory tusks, the occasional thick leather hide, and an exotic cash cow of the sea.

For Further Reading:

Natalie Lawrence's essay "Decoding the Morse: The History of 16th-Century Narcoleptic Walruses"

Mike Jay's New York Review of Unusual Book Binding Materials from Walrus Leather to Human Skin

A History of Human-Walrus Relations in the North Water Polynya

A Study and History of the Walrus in Indigenous Americans' Cultural and Traditional Thought

An Explanation of How Walrus Ivory was Carved in the Middle Ages

Comentarios